It’s a strange New York these days. It’s not particularly scary or sad, but it’s striking that the essence of New York life — energy, noise, action — has been stilled, and now there’s more of a sense of solidarity and resilience, sadness and concern.

From the middle of March, when the Americans finally woke up to the coronavirus crisis, New York has divided on class lines. The rich have fled, to the Hamptons beach communities on Long Island, to their cabins up the Hudson River, to their condominiums in Miami Beach. There, for all intents and purposes, they continue their work, which after all can be done on-line: banking and stock trading, management, communications, sales. One gets the sense that there’s broad anxiety about the future, building on the already pervasive “Trump Derangement Syndrome” (New Yorkers are invariably opponents of the current president) worrying about the future, about what is becoming of America, and oh-my-God does this mean I can’t fly to the Caribbean any more?

The poor, on the other hand, have also departed. They’re losing their jobs as secretaries, cashiers, cooks and bartenders, and have fled home to Queens or New Jersey, sitting at home with their children (who are, of course, not in school) wondering where they’ll find the money for their next rent payment. Not only have they lost their income, but they’ve lost their health insurance (if that had any) and so are doubly concerned about the prospect of an expensive hospital stay if they contract the virus.

Their voices have been stilled, and no one really knows yet how this will translate into political action, or even if it will translate into political action at all. Will they decide now to unite and throw out Donald Trump in November? Or will they see him as their only hope? It’s simply too soon to say, and the shock has not yet worn off.

And so with the rich and the poor out of the way, the rest of us – people like me, retired without enough money to own a second home, but with enough savings to pay the rent for a while – have inherited the island of Manhattan. Yes, there are people on the sidewalks, now most of them wearing masks of some sort. Yes, there are cars and delivery trucks, stores still open (CVS, Trader Joe’s, bars and restaurants sending delivery boys on bicycles throughout the city with take-out orders).

But there are some new things as well: tents being erected in Central Park for virus victims, a U.S. military hospital ship docked on the Hudson River. I live a block from the New York University Hospital, and see the ambulances lined up in front of a new tent for admissions into the emergency room: sirens wail all night. Of course, this is New York: sirens ALWAYS wail all night. But I suspect there are more than usual.

At 7:00 in the evening, every evening, all the people left in Manhattan come out on the balconies of their high rises and clap and cheer; the fire trucks sound their sirens; there’s a broad show of solidarity, something we’ve learned from the Italians. For a few minutes, one weeps with joy to be a New Yorker, and to feel the common cause of representing the diversity of America’s most diverse city, of the breadth and power of who we are and can be. But again, it’s only been a short time, and we don’t yet know how things will turn out.

One theme that has emerged is the power of local authority. The government in Washington has made it a point of faith, in the last three years, to challenge competence, and instead to believe in the heat of loyalty and instinct rather than the cool rationality of experience and knowledge. So it’s no surprise that the current administration has not known how to respond to this crisis, which cannot be solved by bluster or threats. Instead, local authorities have emerged: the governor of the state of New York, Andrew Cuomo, has shown himself to be a tough, down-to-earth, honest leader at a time when that is welcome. There have been similar responses by the governors of California, Michigan, and Ohio, and the mayors of a wide variety of cities throughout the country, hinting that traditional relationships of governance may be changing.

Already more New Yorkers have died from the coronavirus than died on 9/11. The statistics show clearly who is at risk: those over 75 years of age; twice as many men as women; overwhelmingly those who have pre-existing conditions (that is, diabetics, cancer patients, those with weak immune systems). Poor people more than rich people. Life will clearly not be the same after this crisis, one that is not localized but besets us all, around the world, regardless of where we are. In these early days, we see the basis of courage and resilience, but also the fear of some sort of nameless doom, the end of things as we knew them. And we have not yet begun to truly understand the scope of what this will mean: for us, for those we love, and for our friends.

My own optimistic hope is that the instinctive solidarity that New Yorkers have shown for one another grows, and that this instinctive solidarity – which has been in short supply in recent years – becomes a stronger part of all of our lives in the weeks, months, and years to come.

*Cameron Munter is a career diplomat. He served as a United States Ambassador to Serbia and Pakistan, and was the chief executive officer and president of the EastWest Institute.

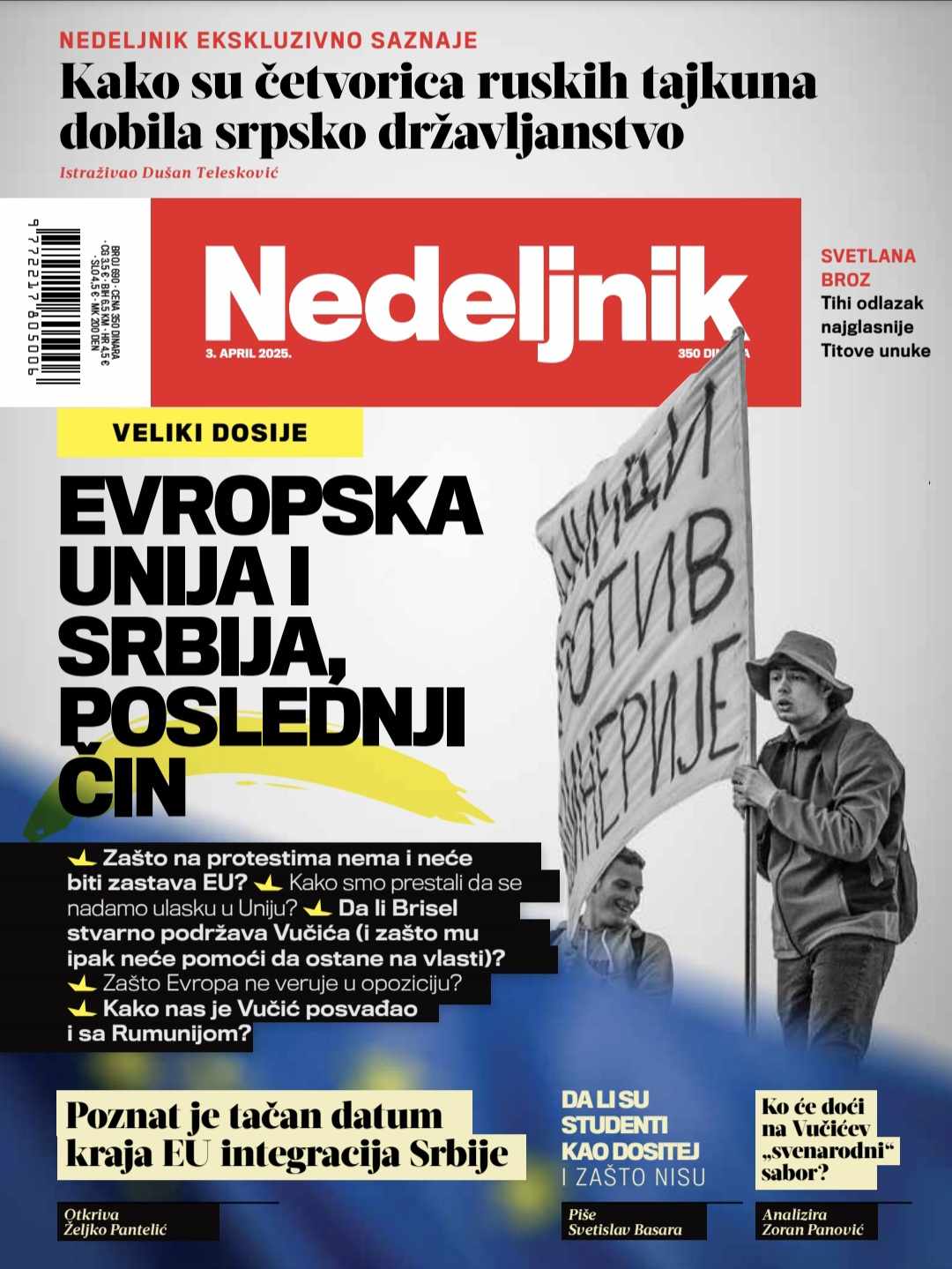

This article was published in Serbian language in the print edition of Nedeljnik, with the headline “Šta nas je kriza dosad naučila: Javljanje instinktivne solidarnosti i nova moć lokalne vlasti”